We Sit In Circles

From the Perspective of a Pacifica Teacher

Conversations are very common. For most of us, they are a regular feature of our daily routines. Some are long; some are brief. Some are mutual and exciting; some are more one-sided and dull. For all their frequency, though, it is rarer that we take the time to ask about the quality of our conversations. It is not often that we think about how we behave in our conversations. We might ask a few questions. Do I tend to initiate or respond? Do I make more statements or ask more questions? Do I attempt to control the conversation? Do I speak only to particular people in a group? All of these questions are potential teaching-moments because they tell us valuable information about our habits.

The tricky thing about conversations, though, is that it is notoriously difficult to reflect upon them accurately. We’ve all had the experience of a heated, engaging, perhaps even frustrating conversation, after which we were quite unable to put into words what precisely happened while we were talking. There is something that can only be experienced in conversation and only approximated outside of it. Because of this, it is important to do what we can to gather data from within the conversation itself so that we can form more accurate reflections and evaluations of conversations afterward.

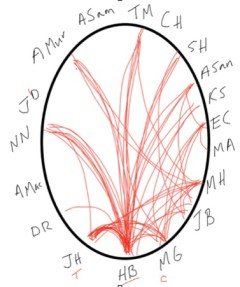

And so we come to the idea of conversation tracking. This is a technique I learned from a very talented sixth-grade teacher I met in Houston, who demonstrated its use while conducting a Socratic seminar with her students on C.S. Lewis’ The Last Battle. By that point in the year, the students had developed the ability to track their conversations, assigning a “tracker” during each class period. What they produced looked like this:

This is an example of a conversation from one of my classes during their third week.

At the outset of the year, students are taught about several types of participation in conversation. There are leading questions, clarifying questions, constructive comments, cohesion comments, and textual references. Students learn about basic table manners, including the importance of looking people in the eye, addressing people by name, employing attentive body language, and listening completely before responding to a person’s comments. Once taught these categories, we begin our class conversations. Each line on the diagram represents one of these discussion actions.

So let’s take a look at this tracking form. First of all, this is not a great conversation. You’ll notice that everyone is pretty much having a series of one-on-one conversations with “HB”–that’s me. Some people aren’t part of the conversation at all. Some people are triangulating the conversation even while sitting next to a quiet person. Others are talking to me as a way of talking to the class. In short, it’s kind of a mess.

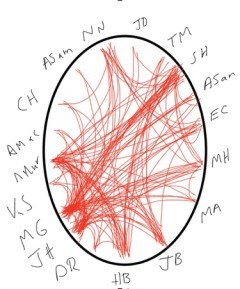

Let’s now take a look at a conversation by the same class from this morning (Week Eight):

Note the changes from five weeks ago. First, there is a greater volume of student contributions to the conversation–everyone added something. Second, the students are talking to each other rather than just to the teacher (HB). Third, the teacher did not have to reboot the conversation.

One of the added bonuses of tracking conversations like this is the ability to allow students to self-advocate and self-examine. These tracking sheets add up over the course of a couple of months, allowing students to review and analyze their habits, which grants them insight into how they might grow into better participants. In the end, the students end up learning how to identify those on the margins and bring them into the conversation. Tracking gives to individual students more awareness of the overall health of their class interaction so that the class learns, over time, to grow together. In short, the conversation does not improve unless the class improves as a team, collaboratively and creatively.

Conversation is something we all experience, and so we might be led to think that it is merely natural and not something upon which we can improve. At the same time, I believe we’ve all sensed when a conversation with others has gone really well. We walked away feeling a bit tired because it took effort, but also feeling rewarded as though we had come to know something new, and also that we had been known in the process. Students are not natural conversationalists; no one starts out able to have these conversations. But they have potential. By making conversation into a conscious habit, students improve in their practice of conversing so that, in time, they are no longer thinking about speaking to one another but are simply conversing and experiencing learning by knowing a subject through knowing each other and being known by others as well.