- Who We Are

- Admissions

-

Academics

- Academics

- Liberal Arts & Sciences

- Our Practices

- Classroom Experience

- Curriculum

- Academic Support

- College Counseling

-

Signature Programs

- Signature Programs

- Summer at Pacifica

- Arts

- Athletics

- Academic Teams

- Declamations Contest

- Houses

- International Travel

- Prefect Board

- Senior Projects

- Service Learning Program

- TGC Honors & Scholars

-

Community

- Community

- Student Life

- Spiritual Life

- Triton Traditions

- The Parent Experience

- The Great Conversation

- Innovation Talks

- Give to Pacifica

- Triton Portal

- Giving

« Back

Shakespeare must have been elated when King James announced, only ten days into his reign, that he would be the new sponsor of Shakespeare’s company. According to the royal patent, Shakespeare’s company would be permitted:

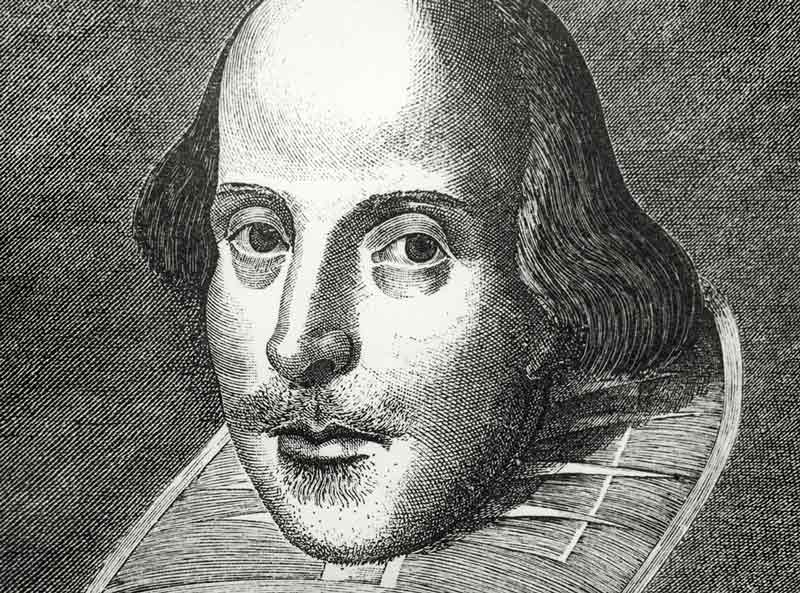

God and Politics in Shakespeare’s Macbeth

October 23rd, 2018

freely to use and exercise the art and faculty of playing comedies, tragedies, histories, and interludes, morals, pastorals, stage plays and such like as they have already studied or hereafter shall use or study, as well for the recreation of our loving subjects, as for our solace and pleasure when we shall think good to see them during our pleasure.

However, a cloud quickly appeared on the horizon, when King James banned theatrical performances on Sundays, as a gesture of support to Puritans. Religious tension was teeming in the city of London, embroiling both the theatres, and England’s monarch. King James, a Presbyterian, was married to a Catholic, and was the son of a Catholic. Shakespeare needed to please both factions, while negotiating two censorial offices to gain permission for performance.

In Macbeth, Shakespeare brilliantly engages the religious tension of the Jacobean culture: the play highlights the Presbyterian conviction regarding the primacy of scripture, as well as tenets of Catholicism -illegal, hidden from the government - but treasured by much of the populace. In Act I, scene vii, Macbeth, not yet overcome by evil, sympathetically quotes a poem from a martyred Jesuit priest named Robert Southwell who had been burned at the stake in 1595. (2)

On the other hand, Protestants would have been moved by the common housewife in the play who shouted, “Aroint thee witch!” This moment in the script moved the plot forward and set the stage for a renunciation of the witches later in the play. It is a direct allusion to the Geneva Bible of 1599’s translation of James 4:7, which exhorts, “Submit yourselves to God: resist the devil, and he will flee from you.” The Bible provided a cultural identity for the ruling Protestant/Presbyterian majority still smarting from the nearly successful Gunpowder Plot of 1605 in which the intended killing of King James was attributed to a Catholic conspiracy.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth deftly met the stringent requirements of The Master of Revels, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and King James. It was, and remains, a crowd pleaser in an era in which religious tension remains an issue. Macbeth spoke to Jacobean audiences offering elements of Protestantism and Catholicism, along with edge-of-your-seat action. Those who see a performance of Macbeth will talk about it long afterward - and may be tempted to leave a light on at night.

(1), Honan, Park. Shakespeare: A Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 298-301

(2), Morris, Sylvia, The Shakespeare Blog, June 23, 2018